Competitive analysis between the two dieting heavyweights

In1944, one hundred men were enrolled into a year-long study which would later be notoriously nicknamed the Minnesota Starvation Experiment. Lead researcher Ancel Keys had hoped to develop a treatise to scientifically back up the grave necessity of the Allied relief fund, which provided assistance to famine victims in Europe and Asia.

In order to do that, he designed a trial investigation to determine the physiological and psychological effects of severe and prolonged dietary restriction and the effectiveness of dietary rehabilitation strategies.

The trial was divided into four distinct periods, involving a standardized 3-month control period for all participants, where they were allowed 3,200 calories a day, followed by the semi-starvation period, where men were only allowed half of their usual ration — 1,560 calories.

After the 6-month period, the subjects were further divided into four groups for another 12 weeks, each group receiving different treatment and were exposed to different dieting schemes. After the entire 48-week period was over, the subjects entered an 8-week period of unrestricted rehabilitation period before they were finally released from the shackles of this truly grueling experiment.

The study’s simplified abstract makes it seem like the 6-month starvation period isn’t so bad, but caloric intake was in fact adjusted per individual to achieve a weight loss of approximately 1.1 kilograms per week, meaning some men, especially those who by nature have lower metabolic rates, received less than 1,000 calories a day.

Because the relief fund would most likely impart with the country’s cheaper produce, the experiment utilized foods that were high in carbohydrates, such as potatoes, turnips, bread, and macaroni. Meat and dairy were rarely given, owing to the downside it would have imposed on the US economy.

This one-year experiment birthed a two-volume, 1,385-page report which contains an extensive analysis of the physiological and psychological data collected during the study.

Among the conclusions, findings were pathological hypothermia (one subject had to wear a sweater on a hot and sunny July afternoon) as body temperature dropped to an average of 35.4˚C (95.7˚F) and physical endurance dropped by half.

Strength was found to have shrunk by 21%, and subjects recalled experiencing a complete lack of interest for anything but food.

All sorts of neurotic behaviors were also observed, as subjects began hoarding cookbooks and other utensils. Two subjects had to be taken off the study after being caught stealing and eating raw turnips and taking scraps of food from garbage cans.

In 1965, Angus Barbieri kicked off an unlikely journey that would end up shattering a world record and surpassing human limits once thought impossible after he completed it 382 days later. What did this respectable Scottish man accomplish? He fasted for over a year. Angus Barbieri lived on black coffee, tea, soda water, and multivitamins living at his humble abode Tayport, while frequently checking in at Maryfield Hospital for medical evaluation.

Angus lost 125 kilograms (276 lbs) as his weight dropped from 207 to 82 kilograms, setting a world record for the longest fast ever (successfully) accomplished. A medical report issued by the Scottish University’s Medical Department said that “the patient remained symptom-free, felt well, and walked about normally”. The man lost an average of 2.3 kilograms a week during his fast, which is more than double that achieved by the Starvation Experiment, and showed no ill-effects on top of that.

To be fair, it’s both scientifically and rationally unwarranted to compare the two cases apple-to-apple. The second case study involved just 1 person, who was in all likelihood a one-of-a-kind outlier and had a substantially higher starting body weight. But it does illustrate some very interesting points about just how different the physiological responses one can get from fasting — eating nothing — compared to eating less.

Dr. Jason Fung, in his book The Obesity Code, stipulates that caloric restriction will result in less weight and fat loss, more muscle loss, and more hunger. Similarly, in Upton Sinclair’s 1911 book The Fasting Cure, he writes about fasting as a means to improve health.

“I was very hungry for the first day — the unwholesome, ravening sort of hunger that all dyspeptics know”, he wrote. “I had little hunger the second morning, and thereafter, to my great astonishment, no hunger whatever — no more interest in food than if I had never known the taste of it.”

Sinclair liked to take long fasts, often up to 12 days or so. Here’s another excerpt from his book backing his choice of longer fasts.

“Several people have asked me if it would not be better for them to eat very lightly instead of fating, or to content themselves with fasts 2 or 3 days at frequent intervals.

My reply to that is that I find it very much harder to do that, because all the trouble in the fast occurs during the first 2–3 days. It is during those days that you are hungry.

Advertisement. Scroll to continue reading.Perhaps it might be a good thing to eat very lightly of fruit, instead of taking an absolute fast — the only trouble is that I cannot do it. Again and again I have tried, but always with the same result: the light meals are just enough to keep me ravenously hungry.”

In the book, Sinclair says you will know when you should finish fasting because your hunger will return. The patients he treats and enrolls in his fasting program usually return to eating after more than 10 days of fasting.

This theory runs contrary to the idea that one would get hungrier and hungrier as long as they don’t eat. However, most people have experienced themselves that this is not the case. Some will find that they are not hungry at all in the morning, or at least not as hungry as lunch or dinner. But consider this, the morning is when you’ve gone the longest without food.

This phenomenon can be partially explained by the hormone ghrelin, which signals hunger to the body by increasing appetite and is sometimes associated with weight gain.

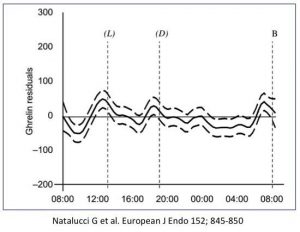

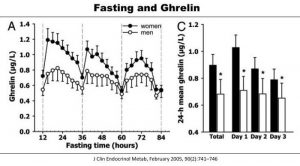

A famous 2005 study by the University of Vienna looked at patients participating in a 33-hour fast while having their ghrelin levels checked every 20 minutes. Ghrelin is lowest at 9 am, which is when they have gone the longest without food. Predictable Ghrelin comes in patterns and overall does not rise during the period the subjects were fasting.

Ghrelin spikes are expected during supposed ‘lunch’ and ‘dinner’ periods (shown as (L) and (D) on the graph), as the body has accustomed to releasing ghrelin during those hours, but drastically drops again just 2 hours after receiving no food.

It may sound illogical and untrue, but you may have experienced this as well, perhaps when you were too busy doing something that you simply skipped an entire meal and not feel hungry afterward.

This is important to acknowledge if you are just starting your fast because you will need to overcome those natural hunger spikes. But as Sinclair repeatedly assures in his book, the hunger will simply go away if you are patient enough.

Another study in Denmark looked at 33 subjects who fasted for 84 hours, just over 3 days. They saw similar ghrelin patterns throughout the day, but total daily production actually decreased the longer they fasted. Going longer without food actually made them less hungry. This idea gives credence to what Upton Sinclair said about hunger disappearing after the initial 3 days of fasting.

Another thing that happens during these fasts is ketosis when your body essentially uses fat to create energy.

Ketosis is mainly popular as a dietary method for weight loss but it also has many other benefits including better physical and mental efficiency. Ketosis occurs when you restrict carbohydrate consumption down to 50 grams or less per day and you don’t eat too much protein, triggering the body to utilize its own fat storage as a source of energy as reserves run low.

The recommended ratio for a ketogenic diet is 5% carbs, 20% protein, and 75% from good, healthy fats.

Another way to enter ketosis is to just stop eating for some time — or in other words, to fast.

This is one other way that caloric restriction differs from fasting. The main problem with the Minnesota Starvation Experiment was that they are eating just enough to keep them out of ketosis and keep their metabolism prime for burning carbs, so they couldn’t exploit their body fat for energy.

Muscle is digested for energy instead, which also explains why they were losing strength and were so sluggish and cold. This goes in line still with Sinclair’s claim that light meals such as fruits were enough to keep him ravenously hungry and far weaker than if he had just been eating nothing.

The interesting thing about carbohydrates is that they stimulate insulin release, and too much of it decreases the secretion of hormone-sensitive lipase, which is necessary to mobilize fat and use it for fuel. Processed refine sugars will cause a higher insulin spike than fruits and vegetables.

Because the body cannot use fat as fuel, the body will simply slow the metabolism down to preserve energy. In the Minnesota Experiment, the subjects’ metabolism dropped on average by 40%. The body did not have access to its stored energy and the restricted caloric diet did not provide much fuel so there was no other choice than to curb metabolism.

Ironically in fasting, as Dr. Jason Fung points out, metabolism actually goes up. A 2000 study showed that the REE (resting energy expenditure) goes up with every additional day of fasting, which means you’re burning more energy than you do without fasting.

If there are no carbohydrates and fat, the body will break down muscle to form glucose through a process called gluconeogenesis. This is obviously bad for the body in the long-term, as shown by the ill-effects it presented to the subjects of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

When the body is unable to access its own stored energy, as in the case with consequentially decreased metabolic rates, it is more likely to resort to this destructive act. Caloric restriction increases the risk of muscle loss.

Fasting also increases the secretion of Human Growth Hormone (HGH), which is an anabolic hormone, and as its name implies, is responsible for growth. A little piece I remembered reading in one of my first-year textbooks on human physiology suggests that “growth hormone also mobilizes large quantities of free fatty acids (FFAs) from fat tissues, which in turn are used to supply most of the energy for the body’s cells, thus acting as a potent protein sparer.” HGH prevents muscles from breaking down. In the Danish study I quoted earlier, HGH rises significantly after the second day of fasting.

One should enter ketosis sometime within the first 3 days of fasting, which depends on a multitude of factors, among which are your level of physical activity and what your diet looked like before starting the fast. Ketosis is a good sign that your body is making good use of its stored energy, and can be evaluated through routine blood work.

Exercise is an adjunct that can help increase HGH release and enter ketosis, and fasting also increases the amino acid leucine, which has an anabolic effect on the body, helping it preserve lean body mass.

To summarise the mammoth list of evidence and facts in this article, fasting appears to be superior to caloric restriction when it comes to weight loss. It can help you lose weight faster through the helping hands of ketosis and retains muscle mass for effectively, as well as preserving energy and keeping you away from hunger with longer duration fasts.

However, it is important to keep in mind that more research is still needed to unearth the long-term effects of fasting, and whether or not it is healthier than a normal diet for healthy and fit adults not intending any weight loss.

Source : Medium

Related

You must be logged in to post a comment Login